- 54. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #9 & 10

- 55. “Happy New Year!” “I don’t say that.”

- 53. Halloween 2019

- 52. READY Workbook Pg. 17

- 51. English-Uplift 1-Day Seminars

- 50. READY Workbook - vocabulary copying activity

- 49. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #8

- 48. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #7

- 47. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #6

- 46. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #5

- 45. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #4

- 44. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #3

- Kindergarten aged students

- Lower Elementary-school aged students

- Upper Elementary-school aged students

- Junior High and older students

- Others

45. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #4

https://www.apricot-plaza.co.jp/en/advice-box/usage-and-methods/jikkkun:

This post will look at #4:

4. Evaluate your lesson on how successful each student feels.

It is important that students feel “I said what I wanted to say in English!”, and this should be the basis of your lesson. Kids tend to speak when placed in a situation that requires them to do so. As you review your lessons, ask yourself “Was I able to provide enough opportunities for the students to speak?”

Whoa, now this is a big one. This point asks teachers to really ask themselves “Why am I teaching English? What do I want my students to achieve by taking my lessons?” In most countries around the world where English is taught as a foreign language, teachers (and students) are very clear on what they want lessons to result in: the ability to speak English. In Japan however, our English education is not geared towards this aim at all.

As you may know, I teach in a small English conversation school for kids in Setagaya, Tokyo. I have a class on Mondays with 5 junior high students. Three of them enjoy speaking out and the seize on every opportunity I provide to do so. The fourth student isn’t really as expressive as her classmates, but will answer any questions addressed to her directly. The other student is fairly new to this class, he is the only boy in the class, and isn’t yet comfortable with speaking out.

Last week, during an activity that required the students to share information in order for the activity to move forward and be completed, the young boy was not cooperating at all, and this was becoming frustrating for the girls because they really needed the information that he had!

Suddenly, the student sitting closest to him leaned over to him and whispered in Japanese: “Hey! Come on! Speak please! This is not school here!”

This comment, I felt, very adequately summed up Japan’s junior high English education: English is not studied as a language for the purpose of speaking it, rather its grammar rules and vocabulary are memorized only for examinations.

My student’s comment to her classmate also confirmed that my lessons were indeed providing an alternative to her school education, and that is what I believe all of us outside the public school system should provide. As Kawahara-Sensei points out, this should be the basis of our lessons – whether we are using LEARNING WORLD with our students or not.

For those teachers who are not used to providing speaking opportunities, who are not sure how to do it, but recognize that their students need it, Kawahara-Sensei gives a big hint:

“Kids tend to speak when placed in a situation that requires them to do so.”

This is exactly right. Kids on the whole will speak when they need to. So creating that need by way of situations in the classroom, is a major responsibility of their teacher.

Try asking students to open their textbooks, but don’t tell them the page number. This situation will elicit “What page?” from the students.

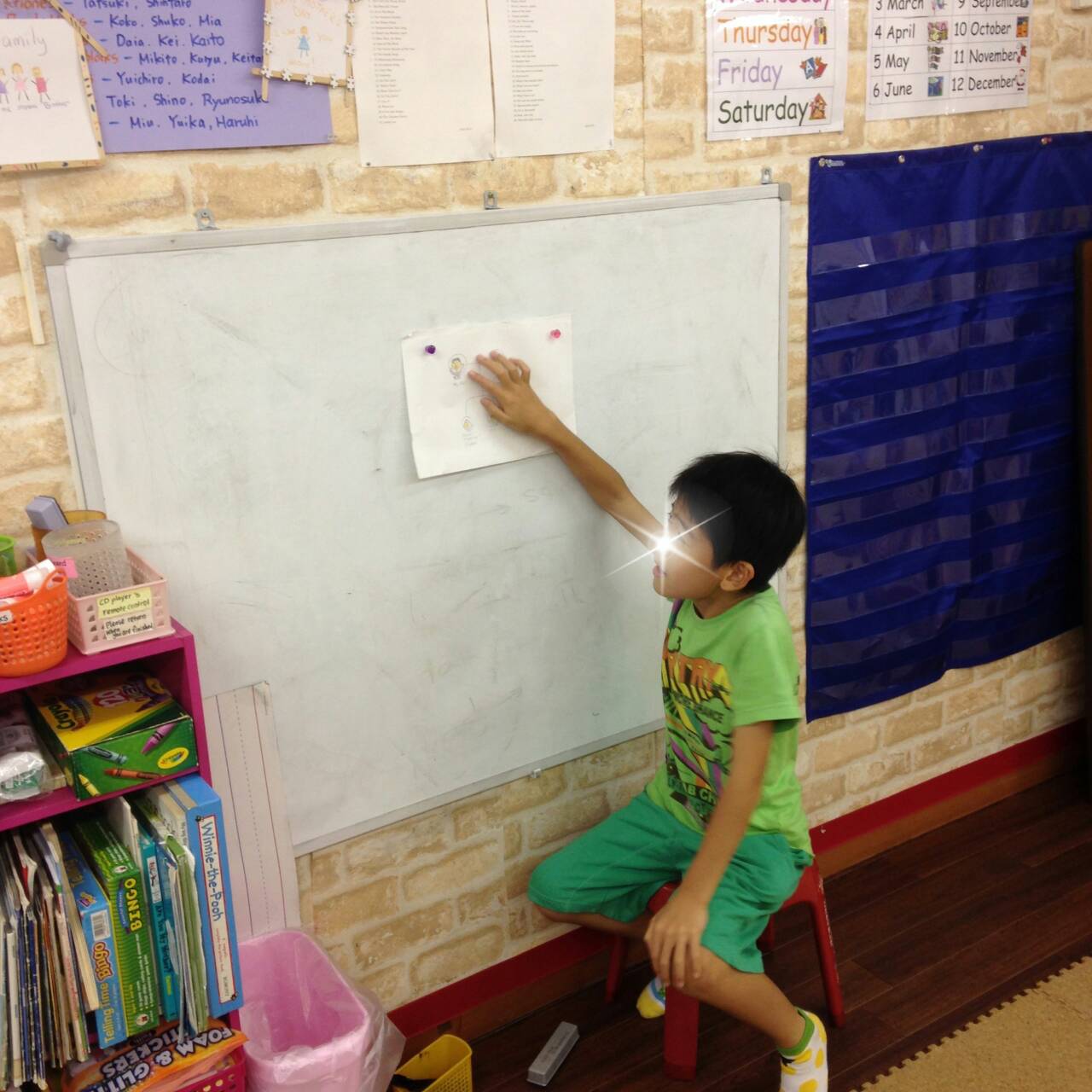

Try standing directly in front of the whiteboard as students are copying information from it into their notebooks. This situation will elicit “Excuse me” from the students.

There are countless situations to create for students in the classroom. Each situation needs to be created for the specific purpose of students’ output. If your students don’t know the English expression for the English you are trying to elicit, then give the expression to them at that time, then try to elicit it from the students in the same situation a short while later.

Eventually the amount of English your students can use will grow, and so will their feeling of success with English.

44. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #3

In the coming days I’ll be posting my thoughts on each of the excellent 10 pieces of advice for Learning World teachers on

https://www.apricot-plaza.co.jp/en/advice-box/usage-and-methods/jikkkun:

This post will look at #3:

3. Don’t skip over the self-expression activities

To be an effective communicator in a foreign language, you need much more than just knowledge of the target language. You need to have communication strategies AND you need to have a positive attitude towards expressing yourself. The culture of Japan is unique and beautiful, and much of it stems from the discouragement of public individual expression. Communication strategies within the Japanese language too are so unlike any other cultures, bordering almost on telepathy. However, the Japanese need to put these beauties to one side if they want to use English as a tool for communication because English, in both language and culture, is not like Japanese at all.

With Japanese English education being so exam-oriented and not focused on communication, it’s no surprise that it gives no thought to strategy and self-expression. But even in many English conversation schools where communication ability is an educational goal, students’ strategy and attitude development is largely ignored.

The self-expression activities in LEARNING WORLD require our students to express an idea that’s unique for each student, and students are then required to present their work to the class. This experience is very valuable for students in at least two very important ways.

Firstly, by having students express an idea that’s unique to each, we as educators are sending them the message that their ideas/thoughts/opinions matter.

Secondly, by having students present their work to the class, we as educators are sending them the message that their ideas/thoughts/opinions have value.

Giving students these beliefs is vital for the development of effective communication because by its very nature communication is the sharing of ideas/thoughts/opinions. Furthermore, in a society that relies on creative talent to solve its problems, it’s imperative that individuals have a positive attitude towards self-expression.

Please don’t skip over the self-expression activities in LEARNING WORLD. They are vital “attitude-development exercises”. Over time you may find that students who have experience with these activities tend in class to speak out more than those students with little experience.

43. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #2

In my last post I wrote about the necessity of reminding ourselves as teachers of what’s important when teaching Learning World, and the “10 pieces of advice for Learning World teachers” on the APRICOT homepage – https://www.apricot-plaza.co.jp/en/advice-box/usage-and-methods/jikkkun – is really good for this. Over the coming days I’ll be posting my thoughts on each piece of advice.

My last post gave recognition to #1:

1. Focus on your own vision!

This post will look at #2:

2. Communication activities are a must!

“Communication activities are a must”? Yes. Absolutely.

It should be pointed out that just because teachers and students are speaking English in the classroom, it doesn’t necessarily mean that communication is happening. In a good many classrooms around Japan – in both the public and the private sectors – there is a lot of English being practiced but very little English being used. Communicating in English means using English. And if there is any expectation that our students need to be able to communicate in the future, then they need communication experience within their English education NOW!

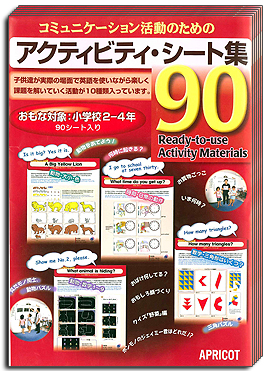

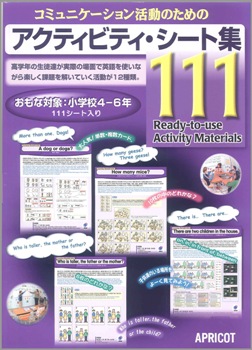

The communication activities published by APRICOT (“Kara-Kyogu” and “Activity Sheets”) are mostly in a game-like format and therefore the communication is more structured and not as genuine as real-life situational communication, nevertheless they offer highly valuable English experiences for our students. APRICOT can most certainly be excused; after all, how does one go about publishing actual real-life situational communication, anyway?!

Yes, I agree totally with this second piece of advice for Learning World teachers.

Bring communication activities for your students now, and then again the next lesson, and then every lesson again thereafter!!

42. 10 Useful Pieces of Advice for Teaching with LEARNING WORLD #1

Not a lot happens in the classroom during Summer Vacation… so it’s a good time of year to for to remind ourselves of Learning World’s important things – things that we can sometimes forget when during the year’s busy months. And there is a new page on the APRICOT web site that can help us do just that:

https://www.apricot-plaza.co.jp/en/advice-box/usage-and-methods/jikkkun

On this page Kawahara Hiromi-Sensei has put together 10 useful pieces of advice for teaching with Learning World.

1. Focus on your own vision!

2. Communication activities are a must!

3. Don’t skip over the self-expression activities.

4. Evaluate your lesson on how successful each student feels.

5. A Textbook is not everything!

6. Importance of reviewing

7. Make students use English

8. Respect individuality!

9. Do not fear to show your weaknesses!

10. I’m right – and you’re right too.

To my mind “Useful Advice” is a major understatement. These points express the very core of Learning World education. Over the coming days I’m going to post my thoughts on each one, starting with the first one:

1. Focus on your own vision!

Kawahara-Sensei explains “Language education with kids is long-term. Never forget WHY you are teaching English to children.”

Yes. I’ve found that many teachers go through the motions of teaching English without a clear vision of the long-term objective. They attend workshops and seminars for hints and tips on “HOW” but not knowing “WHAT FOR”.

As a teacher once you have a clear goal of what you want to achieve for your students, you begin to question the purpose of all your actions in the classroom. For teachers this is an extremely healthy process that gives incredible growth and maturity to your teaching.

In my case, once I realized the difference between when my students “used” English as opposed to when they “practiced” English, my long-term vision became clear. With this new vision, I dramatically reduced the amount of “repeat after me” time in the classroom, and as a result the students immediately began to produce more English!

Yes, I agree totally with this first piece of advice. Know your vision for the future, and focus on it!

41. Escargots

There was discussion in our classroom yesterday about snails. My team-teacher colleague turned to the class and said “You know in France, people eat snails”. One of the students gasped audibly and asked “What?? Only snails??”

It took me a good minute to stop laughing. Children often show comical brilliance that professional comedians would die for.

But actually even before that student’s reaction, I was already feeling somewhat uncomfortable with my colleague’s remark.

“You know in France, people eat snails”.

He was clearly referring to the dish “Escargots” and understandably using the main ingredient (snails) for simplicity, but it was the “In France, people…” part that bothered me.

I immediately thought of my wife who is an ardent fan of Escargots and will tend to order it whenever she finds it on a restaurant menu – which she does, and not always at French restaurants either. Now my wife lives very comfortably with me here in Japan, not France, so my colleague’s education to the class discounted her – as well as the countless other lovers of the dish in this country, of whom I assume there are many. After all, if there weren’t many, Escargots wouldn’t appear on menus here at all, right?

“You know in France, people eat snails”.

After thinking about my wife, my thoughts turned to people in France. My colleague’s declaration strongly implies that in France all people eat snails. I can’t claim to know all the people in France, so I can’t with certainty dispute my colleague’s claim. But I do know many people in Japan on a personal level who don’t eat sushi, so the comparatible “In Japan, people eat raw fish” would be inaccurate.

Am I perhaps thinking too deeply about this? Wasn’t my colleague simply trying to make an interesting yet innocent point of cultural difference to the class? Yes, I’m sure he was. But if we don’t think about the implications of what we say regarding cultural differences to our students, our education most certainly contributes to unhelpful, misleading and inaccurate stereotyping.

So let’s consider improving the accuracy of my colleague’s wording.

How about “In France, some people eat snails.” This is more accurate, but it still ignores the millions of people all over the world that enjoy the dish.

So we’re left with:

“Some people eat snails”.

For many teachers the lesson inside the line “Some people eat snails” would not be a lesson on International Understanding because it omits the country name. I would argue that it’s a perfect lesson on International Understanding precisely because it omits a country name.

International Understanding has little to with country names, and has everything to do with understanding the people with whom our students share this planet.

So much of Japan’s International Understanding education is accompanied with lines like “People in this country do this, people in that country do that…” But to understand people on an international level is to understand the similarities and differences of people totally regardless of where they are or where they are from.

I strongly believe that teachers should make a conscious decision to omit country names when teaching cultural differences of people. The simple phrase “Some people…” is fine. In this way our students can get more accurate information and avoid unuseful stereotyping.

I’m getting hungry… Escargots, anyone?